The Cleveland Cavaliers are poised to start their 50th season in the NBA, a stretch that’s included plenty of lean years and a number of high points.

Of course, the all-time highlight came in 2016 with their first and only NBA title. Yet the start of the franchise in 1970 was years in the making, with countless bids for a team before that were shot down for a number of reasons.

The NBA’s first season (known as the Basketball Association of America) had a Cleveland team, the Rebels, in it. However, financial losses resulted in the team suspending operations, which relegated the city to the status of a one-shot stopover town for much of the next quarter century.

A Casual Acquaintance

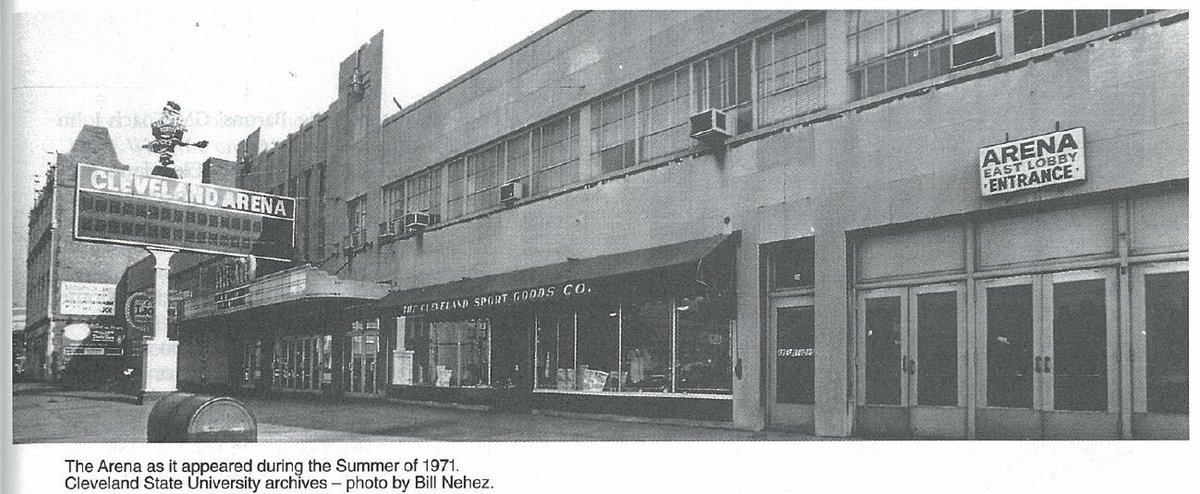

Single games in 1953 and 1954 at Cleveland Arena, followed by a long drought of close to a decade, left local fans with television as their only option to watch the NBA. Then, a small handful of Detroit Pistons and Cincinnati Royals games during the 1963-64 and 1964-65 seasons found their way to Cleveland.

For three seasons beginning in 1966, the Royals then agreed to play one game against each NBA team at Cleveland Arena, with the 1969-70 schedule only consisting of five contests. The games were seen as an aid for the financially ailing franchise and a testing ground for a possible NBA Cleveland franchise.

Basketball Pipers Dream

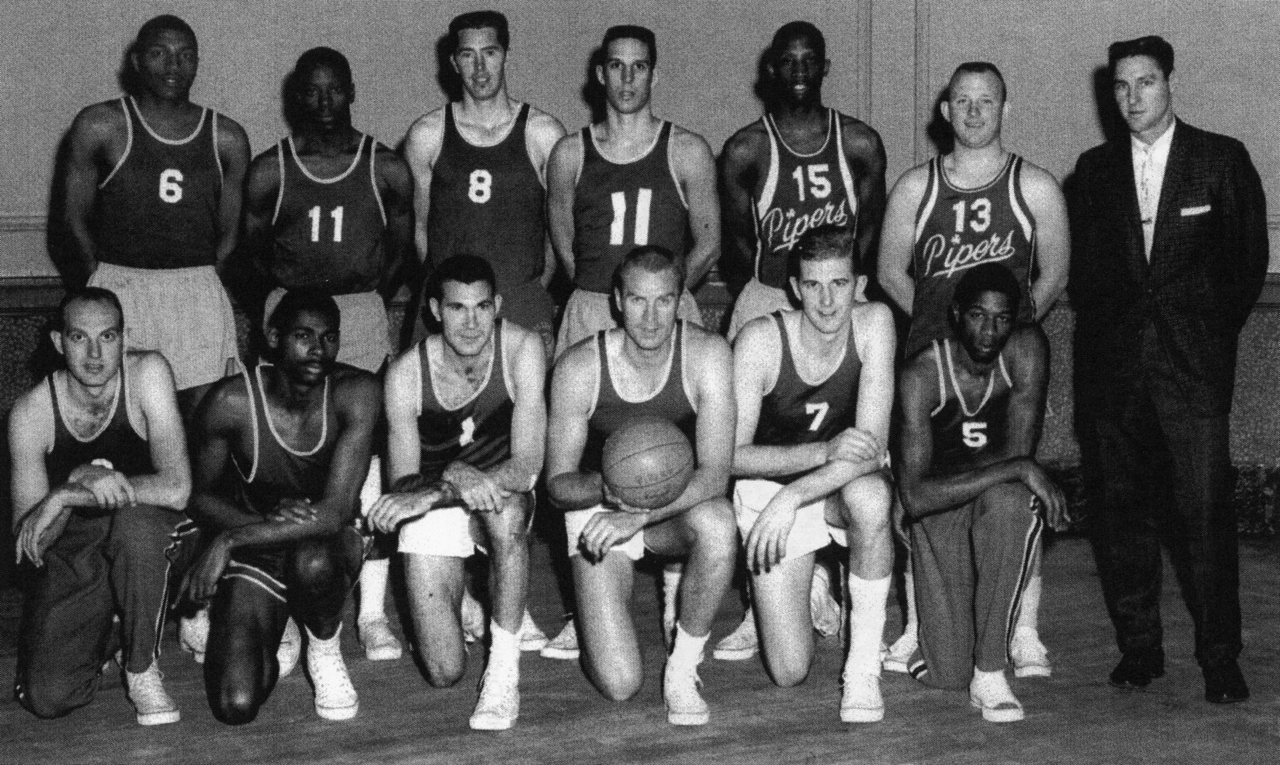

Yet local fans had reasons to doubt that the city would ever have its own team, given all the past disappointments in that department. That included a young George Steinbrenner trying to get his American Basketball League (ABL) Cleveland Pipers team into the NBA in 1962.

The Pipers won the first and only ABL title that year and then signed college basketball superstar Jerry Lucas. However, Stenbrenner lacked the necessary finances to make the jump and folded the franchise. That resulted in a local pair of business executives, Howard Marks and Carl Glickman, picking up the mantle by trying their luck at the same goal, though the Pipers nickname was jettisoned.

Marks and Glickman signed Lucas to a personal services contract in August 1962 and applied for an NBA expansion team. In competition with Baltimore, Kansas City and Philadelphia, the duo dropped out on Jan. 16, 1963, after severe restrictions were placed by the league regarding how the proposed team’s roster would be put together.

The process ended with no expansion, but shifts of the Chicago Zephyrs to become the Baltimore Bullets (now Washington Wizards) and the Syracuse Nationals to become the Philadelphia 76ers.

Pushed Away

Glickman would also be part of the next effort at the NBA, which developed in June 1965 and was focused on the league’s proposed expansion in 1966. Leading the efforts were two other Cleveland businessmen, Ted Bonda and Howard Metzenbaum, with NBA commissioner Walter Kennedy seemingly positive about the city’s chances.

“Our people like Cleveland for three reasons,” Kennedy told the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “One, it’s a fine marketing area. Two, we believe there is great basketball interest there. Three, it’s geographically desirable for the league.”

However, NBA owners refused to meet with Metzenbaum when it was determined that he didn’t have a lease in place to play at Cleveland Arena. The end result was that he ended his efforts following the snub and the NBA instead welcomed the Chicago Bulls into the fold.

Same Old Song and Dance

With the growing league seeking two more franchises for both the 1967-68 and 1968-69 campaigns, it was seemingly a foregone conclusion that the city would be one of the four choices. Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell, who had helped bring the Royals’ games to Cleveland Arena, was expected to become a key part of the ownership group.

A November 1966 Plain Dealer headline declared, “NBA Franchise Due Here in ’68,” with the article’s opening paragraph stating:

“Cleveland is virtually assured a franchise when the National Basketball Association expands to 12 teams for the 1968-69 season.”

Kennedy again offered high praise for the city and cited positive ticket sales for the Royals’ games as evidence of solid fan support. Yet it was Seattle and San Diego that beat out Cleveland and Pittsburgh in 1967, and Milwaukee and Phoenix that emerged from a group the following year.

In the latter case, Cleveland joined Atlanta, Kansas City and Portland as also-rans, though Atlanta ended up with the St. Louis Hawks after they moved in May 1968.

Pinpointing the Issue

In both of those cases, problems with Cleveland Arena served as the key stumbling block. The 30-year-old building needed to be refurbished and the lease that strongly favored the city’s American Hockey League (AHL) team had to be made more flexible in order for the NBA to set up shop in Cleveland.

Another Option?

The level of frustration with the NBA led some to champion bringing a team from the fledgling American Basketball Association (ABA) to the city. An expansion franchise went from “90 percent official,” according to an August 1968 Plain Dealer article to quickly fading away.

Meanwhile, the ABA’s Houston Mavericks considered shifting operations to Cleveland, but instead stayed put before becoming the Carolina Cougars the following year. Those who remained focused on an NBA team feared that bringing an ABA team would disqualify Cleveland from any further consideration from the league’s owners.

Change Arrives

The arena issue was finally addressed through remodeling and a September 1968 ownership change for the facility. Local attorney Nick Mileti bought both the arena and the AHL Barons and soon began taking steps toward adding an NBA team to help keep his building busy.

That push picked up speed at the start of 1969 began and by November of that year, Mileti met with Kennedy about obtaining one of the two (later three) expansion franchises.

“Of course, we’re interested in bringing major league basketball to Cleveland, but as of right now, nothing has been determined about price or player procurement,” said Mileti.

Heartbreak Before Success

Despite there being no guarantee that the NBA would even expand, Mileti met with owners in Philadelphia during the annual All-Star festivities in January 1970.

However, after the league raised the franchise entry price by $500,000 to $3.5 million, limited the money from the upcoming $6 million national television contract and made acquiring players more difficult, Mileti was ready to bolt. Instead, he delivered a compromise proposal.

That led to a meeting in Los Angeles on Feb. 6 in which the NBA owners agreed to Mileti’s plan, which increased the amount of television money the expansion clubs would get. That resulted in Cleveland, Buffalo and Portland growing the size of the league to 17 teams.

“Cleveland is my town and it’s a big league town,” said Mileti after the announcement. “We have pledged to bring big league basketball here.”

Growth Takes Time

It would be a while before the Cavaliers resembled big league basketball, but with nearly a half century in the books, it’s clear that the excitement of the NBA is part of the Cleveland experience. Trying to determine what its centennial season in 2069-70 will look like requires just as much imagination as was needed 50 years ago.